JAGUAR

Panthera onca

Jaguars have a vocal repertoire varied from snarls and growls to “roars” that are more like hoarse coughs or grunts.

As the largest cat native to North America and the third largest cat in the world, the jaguar ranges from Arizona to Argentina and has long been esteemed for its unequivocal power and striking beauty.

“Around the campfires of Mexico there is no animal talked about, nor more romanticized and glamorized, than el tigre. The chesty roar of a jaguar in the night causes men to edge toward the blaze and draw serapes tighter. It silences the yapping dogs and starts the tethered horses milling. In announcing its mere presence in the blackness of night, the jaguar puts the animate world on edge. For this very reason it is the most interesting and exciting of all the wild animals of Mexico.”

– A. Starker Leopold, Wildlife of Mexico

Did You Know?

• Jaguars once roamed as far north as the Grand Canyon

• Seven jaguars have been seen in Arizona and New Mexico since the mid-1990s

• Jaguars have blue eyes when they are born

• Jaguars have the largest eyes of all carnivores relative to head size

• Jaguars in the northern range are smaller than their South American relatives

• Jaguar spots act as camouflage, which help them while stalking prey

• Jaguars are one of the few wild cats with melanistic individuals

Identification

Jaguars have golden yellow-brown fur with dark rosettes unique to each cat. There can be small, irregular shapes within these larger markings, an easy way to distinguish jaguars from leopards. Spots on the head and neck are generally solid, same with the tail where the spots join to form bands. Sometimes called tigre mariposo, the patterns can conjure images of butterflies.

Jaguars have the most powerful jaws of any cat relative to body size and pierce their prey’s skull or neck from behind with one swift bite. Strong climbers and excellent swimmers, jaguars tire quickly and rely on proximity rather than speed while hunting. More than 100 species have been recorded in their diet, including deer, javelina, coati, turkeys, turtles, snakes, and fish.

Jaguars’ saucer-sized tracks are unmistakably round, both the pad and the four toes that touch the ground. Tracks from the front feet are larger and rounder; the hind more elongated and symmetrical. As with other cats, claws do not often register. A jaguar’s tracks could easily be confused with those of a mountain lion, but clear jaguar prints are more robust.

Solitary

Jaguars are almost always solitary, except during courtship and mating. A female jaguar’s territory can be shared with other females, and, in northern Mexico, can be up to 75 square miles. The home range of a male can cover 1.5 times as much area. Scrape marks, urine, and feces are used to define territories.

Mating

Jaguars will mate any time of year, although births tend to coincide with the rainy season. Females reach sexual maturity at two years of age, males at three or four. Following a roughly three-month gestation period, a female will give birth to a litter of one to four cubs, which she will raise alone.

Cubs

Jaguars are blind at birth, and they will not leave their den for several weeks. The cubs learn how to hunt after six months and stay with their mothers for up to two years before setting out to find their own territories. The mother will not tolerate adult males nearby, since a male jaguar could kill her young.

The Maya believed if you spread out the skin of a jaguar, the evening sky appeared in front of you. The jaguar’s coat was a map to the celestial heavens. It was the jaguar who helped the sun travel under the Earth at night, ensuring it would rise each morning.

Threats

Jaguars face immediate and direct threats that require our sustained action to save them.

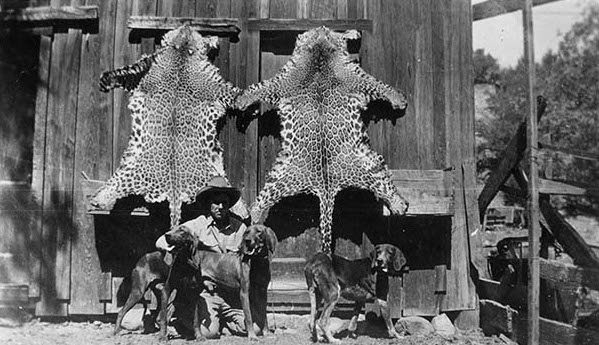

Dale Lee with two jaguar hides in Sonora, Mexico, in 1935

POACHING & POISON USE

Poison is widely used to target large predators, yet kills indiscriminately.

HABITAT LOSS & FRAGMENTATION

In Mexico, jaguars have lost more than 60 percent of their historic range.

DROUGHT & CLIMATE CHANGE

Prolonged drought can make this arid region unfavorable for jaguars and their prey.

HUMAN-WILDLIFE CONFLICTS

Cattle deaths, whether from depredation or another cause, can lead to quick retaliation.

Corridors & Connectivity

Thirteen jaguars from the Northern Jaguar Reserve have also been photographed in locations elsewhere in Sonora

The Northern Jaguar Reserve provides a core sanctuary. The Viviendo con Felinos ranches radiate outward to form a protected buffer zone. The next layer in an ever-widening circle is to establish passageways to connect these hotspots with other conservation lands in the region, such as Rancho El Aribabi, Cuenca Los Ojos, and the Reserva Monte Mojino.

Habitat connectivity is essential for jaguar survival and recovery. Corridors facilitate gene flow and provide big cats with the ability to access resources, find mates, and adapt to a changing climate, including rising temperatures and extended drought. Pathways kept open create a bridge for animals to safely wander and cover immense territories.

In the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, binational conservation organizations are working together to identify priority habitats and key travel corridors – based on factors like vegetation type, proximity to water, and prey availability. This Borderlands Linkages Initiative seeks to secure a network of ecologically rich areas that spans the Sky Island region and northern Sierra Madre Occidental.

Like all large predators, jaguars need broad swaths of unbroken expanse in which to roam. They face challenges as the borderlands become increasingly fragmented, divided by highways, exploited for minerals, and bisected by a border wall that blocks their movements.

Mexican Highway 2 runs near the international border and presents a perilous obstacle for jaguars and other species through its expansion and high speeds. Conservation groups have advocated for wildlife crossings to mitigate the risk of collisions.

Proposed mining within the jaguar’s northern range, particularly the Rosemont Copper mine in Arizona’s Santa Rita Mountains and lithium extraction in Sonora, threatens to scar the landscape and destroy thousands of acres of viable jaguar habitat.

The U.S.-Mexico border wall is an impenetrable barrier for wildlife. Accompanying infrastructure, roads, and high-powered lighting further wreak havoc and damage fragile ecosystems. Although some pockets remain, critical jaguar corridors have been cut off by border wall construction.

RESOURCES

The Border Wall in Arizona and New Mexico – Wildlands Network StoryMap (2021)

Embattled Borderlands – Krista Schlyer / Borderlands Project StoryMap (2017)

Endangered Species, and the Wall That Could Silence Them – USA Today feature (2017)

Losing the Jaguar: Reporting on the Border – USA Today podcast (2017, audio)

Un-Fragmenting / Des-Fragmentando: Reuniting Culture and Ecology in the Borderlands

We oppose efforts that sever wildlife populations already at risk. We must repair what damage has been done, reopen wildlife corridors, invest in restoration, and engage in cross-border collaboration to permanently protect these wild lands.

Photos: Arizona Historical Society, Brendon Kahn, M. Jenea Sanchez, Laiken Jordahl