The Northern Jaguar Reserve was in its infancy when a young female jaguar strolled by one of our motion-triggered cameras in 2006. This first-ever glimpse of a jaguar cub would precipitate the reserve’s expansion to the much larger area safeguarded today.

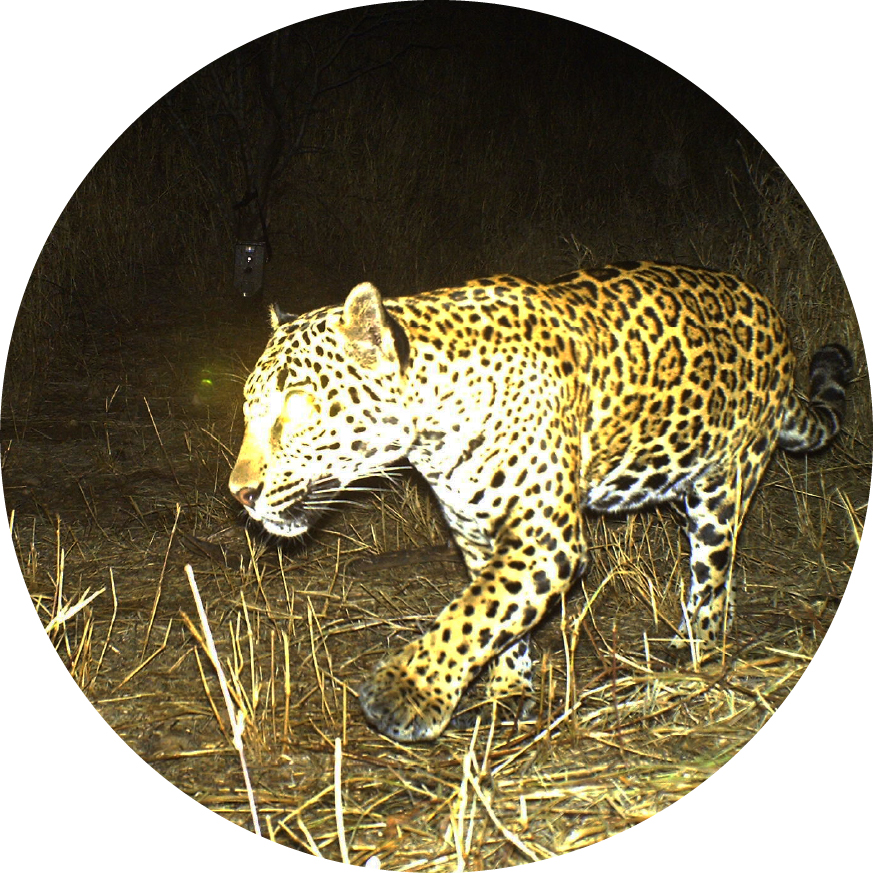

Three years later, in 2009, the cub re-appeared as a beautiful, sleek adult. We named her Corazón for the distinctive heart-shaped spot on her left shoulder.

During the next five years, she was photographed on the reserve 30 more times. Highlights include Corazón carrying a javelina kill and pictures of her on the same camera as the male jaguar El Inmenso only days apart.

Corazón was at home on the reserve. We followed her footsteps as she raised at least three litters of cubs, and her ongoing presence gave us certainty that on the reserve, jaguars were safe. We soon learned Corazon’s territory included locations outside of the protected area.

2011 photo courtesy of Jesus F. Moreno Martinez / Primero Conservation

Researchers from the Instituto de Ecología at UNAM, Mexico’s national university, began working with La Asociación para la Conservación del Jaguar en la Sierra Alta de Sonora. To the north and east of the reserve, they trapped, collared, and released two jaguars – a male collared in 2012, and a female in 2013. This was Corazón.

Corazón on Northern Jaguar Reserve, 2011

Then the unthinkable happened. In 2014, Corazón’s radio collar transmitted the death signal. She had been killed, with poison, and her body burned. To further this tragic blow, small jaguar tracks indicated she had a cub nearby. The cub could not have survived without her.

The private ranch where Corazón died does not border the reserve nor is it one of the Viviendo con Felinos ranches within the reserve’s immediate buffer. Although the rugged, roadless terrain presents a barrier for human travel, a jaguar can cross the mountainous landscape with ease.

A formal investigation was launched. The National Expert Group on Jaguars, a government advisory body, put pressure on the authorities to set an example of no-tolerance for killing endangered wildlife. To date, no one in Mexico has been convicted for killing a jaguar, despite the species having full protection by law.

At the time of Corazon’s death, we knew her more intimately than any other jaguar. She grew up on the reserve, and the reserve grew with her. Corazón’s death was a tremendous loss for the northern jaguar population, a personal loss for us, and we continue our work in her memory.